|

| |

|

Summary of Events In the decade before 1914, Russia was in a troubled state. The tsar Nicholas II(1894-1917) insisted on ruling as an autocrat (someone who rules a country as he sees fit, ignoring such constraints as parliaments) but had failed to deal adequately with the country's many problems. Unrest and criticism of the government had reached a climax with the Russian defeats in the war with Japan (1904-5) and in 1905 had burst out in a general strike and an attempted revolution, forcing Nicholas to make concessions (the October Manifesto) including the granting of an elected parliament (Duna). When it became clear that the duma was ineffective, unrest increased and culminated, after the disasters of the First World War, in two revolutions, both in 1917. The first (March) overthrew the tsar and set up a moderate provisional government; but when this fared no better than the tsar, it was itself overthrown by the Bolshevik revolution (November). The new Bolshevik government was shaky at first and its opponents' (Whites) attempts to destroy it caused a civil war (1918-20). Thanks to the leadership of Lenin and Trotsky, the Bolsheviks (now calling themselves communists) survived and Lenin was able to begin the task of leading Russia to recovery (until his death in 1924).

|

|

|

3.1 AFTER 1905: WERE THE 1917 REVOLUTIONS INEVITABLE? [There was a Revolution in 1905, which Nicholas survived by publishing the October Manifesto, in which he promised to accept a Duma – a kind of parliament.] Nicholas had survived 1905 because his opponents were not united, because there was no central leadership (the whole thing having flared up spontaneously) and because he had been willing to compromise at the critical moment. Tsarism now had a breathing space in which Nicholas had a chance to make a constitutional monarchy work, and to throw himself in with the people demanding moderate reforms: improvements in industrial working conditions and pay, cancellation of redemption payments (annual payments to the government by peasants in return for their freedom, following the abolition of serfdom in 1861), which had reduced over half the rural population to abject poverty, more freedom for the press, and genuine democracy in which the Duma would play an important part in running the country. Unfortunately, he seems to have had very little intention of keeping to the spirit of the October Manifesto, having agreed to it only because he had no choice. The First Duma (1906) was not democratically elected, for although all classes were allowed to vote, the system was rigged so that landowners and middle classes would be in the majority. Even so, it put forward far-reaching demands such as confiscation of large estates, a genuinely democratic electoral system and the right to approve the tsar's ministers. This was far too drastic for Nicholas who had the Duma dispersed by troops after only ten weeks. The Second Duma (1907) suffered the same fate, after which Nicholas changed the franchise, depriving peasants and urban workers of the vote. The Third and Fourth Dumas were much more conservative and therefore lasted longer, covering the period 1907 to 1917. Though on occasion they criticised the government, they had no real power, since the tsar controlled the ministers and the secret police. Some foreign observers were surprised at the ease with which Nicholas ignored his promises and dismissed the first two Dumas without provoking another general strike. The fact was that the revolutionary impetus had subsided for the time being, and many leaders were either in prison or exile. This, together with the improvement in the economy beginning after 1906, has given rise to some controversy about whether or not the 1917 revolutions were inevitable.

(a) One theory is that given time plus gradually improving living standards, the chances of revolution would fade, and that if Russia had not become disastrously involved in the First World War, the monarchy might have survived; three areas of evidence support this view: (i) Peter Stolypin, prime minister from 1906 to 1911, made determined efforts to win over the peasants believing that given twenty years of peace there would be no question of revolution. Redemption payments were abolished and peasants encouraged to buy their own land (about 2 million had done so by 1916 and another 3.5 million had emigrated to Siberia where they had their own farms). As a result there emerged a class of comfortably-off peasants (called kulaks) whom, Stolypin hoped, the government could rely on for support against revolution. (ii) As more factories came under the control of inspectors, there were signs of improving working conditions, and as industrial profits increased, the first signs of a more prosperous workforce could be detected. In 1912 a workers' sickness and accident insurance scheme was introduced. (iii) At the same time the revolutionary parties seemed to have lost heart: they were short of money, torn by disagreements, and their leaders were still in exile.

(b) The other view is that, given the tsar's deliberate flouting of his 1905 promises, there was bound to be a revolution sooner or later and the situation was deteriorating again long before the First World War. The evidence to support this view seems more convincing: (i) By 1911 it was becoming clear that Stolypin's land reforms would not have the desired result, partly because the peasant population was growing too rapidly (at the rate of 1.5 million a year) for his schemes to cope with, and because farming methods were too inefficient to support the growing population comfortably. The assassination of Stolypin in 1911 removed one of the few really able tsarist ministers and perhaps the only man who could have saved the monarchy. (ii) There was a wave of industrial strikes set off by the shooting of 270 strikers in the Lena goldfields (April 1912). In all there were over 2000 separate strikes in that year, 2400 in 1913, and over 4000 in the first seven months of 1914 - before war broke out. Whatever improvements had taken place, they were obviously not enough to remove all the pre-1905 grievances. iii) Apart from one or two exceptions there was little relaxation of the government's repressive policy, as the secret police rooted out revolutionaries among university students and professors and deported masses of Jews, thereby ensuring that both groups were firmly anti-tsarist. The situation was thus particularly dangerous since peasants. industrial workers and intelligentsia were all alike discontented. (iv) As 1912 progressed, the fortunes of the various revolutionary parties, especially the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks, revived. Both groups had developed from an earlier movement, the Social Democrat Labour Party, which was Marxist in outlook. (Karl Marx (1818-83) was a German Jew whose political ideas were set out in The Communist Manifesto (1848) and Das Kapital (1867). He believed that economic factors are the real cause of historical change, and that workers (proletariat) are everywhere exploited by capitalists (middle-class bourgeoisie), which must inevitably lead to revolution and the setting up of `the dictatorship of the proletariat'.) One of the leaders was Vladimir Lenin who helped to edit the revolutionary newspaper Iskra (The Spark). It was over an election to the Iskra editorial board in 1903 that the party had split into the Lenin supporters, the Bolsheviks (the Russian for `majority') and the rest, the Mensheviks (minority). Both believed in strikes and revolution, but the Bolsheviks felt it was essential to win the support of peasants as well as industrial workers, whereas the Mensheviks, doubting the value of peasant support, favoured close co-operation with the middle class; Lenin was strongly opposed to this. In 1912 appeared the new Bolshevik newspaper Pravda (Truth), which was extremely important as a means of publicising Bolshevik ideas and giving political direction to the already developing strike wave. (v) The royal family was discredited by a number of scandals. It was widely suspected that Nicholas himself was a party to the murder of Stolypin, who was shot by a member of the secret police in the tsar's presence during a gala performance at the Kiev Opera; nothing was ever proved, but Nicholas and his right-wing supporters were probably not sorry to see the back of Stolypin, who was becoming too liberal for their comfort. More serious was the royal family's association with Rasputin, a self-professed `holy man', who made himself indispensable to the Empress Alexandra by his ability to help the ailing heir to the throne, Alexei. This unfortunate child had inherited haemophilia from his mother's family, and Rasputin had the power, apparently through hypnosis, to stop the bleeding whenever Alexei suffered a haemorrhage. Eventually Rasputin became a real power behind the throne, but attracted public criticism by his drunkenness and his numerous affairs with court ladies. Alexandra preferred to ignore the scandals and the Duma's request that Rasputin be sent away from the court (1912). According to Richard Freeborn, there was a `growing agitation among the workers, which, in July 1914, in St Petersburg, had assumed the proportions of incipient revolution with street demonstrations, shootings and the building of barricades'. However, the government still controlled the army and police and may well have been able to hold on even if a full-scale revolution had developed. What historians are sure about is that Russian failures in the war made revolution certain and caused troops and police to mutiny so that there was nobody left to defend autocracy. The war revealed the incompetent and corrupt organisation and the shortage of equipment; it caused tremendous social upheaval with the recruitment of 15 million peasants and ruined the economy, bringing rising prices and chronic food shortages. Nicholas made the mistake of appointing himself supreme commander (August 1915) and thus drew upon himself the blame for all future defeats, and for the high death rate, which destroyed the morale of the troops. Even the murder of Rasputin by a group of aristocrats (December 1916) could not save the monarchy.

3.2 THE TWO REVOLUTIONS: MARCH AND NOVEMBER 1917 The revolutions are still known in Russia as the February and October Revolutions. This was because the Russians were still using the old Julian calendar which was 13 days behind the Gregorian calendar used by the rest of Europe. Russia adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1918.

(a) The first revolution began spontaneously on 8 March when bread riots broke out in Petrograd (St Petersburg). The rioters were quickly joined by thousands of strikers from a nearby armaments factory, and when troops were ordered to open fire they refused and joined in the demonstrations. Mobs seized public buildings, released prisoners from jails and took over police stations and arsenals. Some of his senior generals told Nicholas, who was on his way back to Petrograd, that he would have to renounce the throne; on 15 March, in the imperial train standing in a siding near Pskov, the tsar abdicated in favour of his brother, the Grand Duke Michael; when he refused the throne, the Russian monarchy was at an end. There had been nothing organised about this first revolution; it was simply a spontaneous reaction to the chaotic situation which the imperial government had allowed to develop.

|

|

|

(b) The provisional government The Duma, struggling to take control, set up a mainly liberal provisional government with Prince George Lvov as prime minister; in July, he was replaced by Alexander Kerensky, a moderate socialist. The new government was just as perplexed by the enormous problems facing it as the tsar had been, and in November a second revolution took place which removed the provisional government and installed the Bolsheviks.

(c) Why did the provisional government fall from power so soon? (i) It took the unpopular decision to continue the war, but the June offensive, Kerensky's idea, was another disastrous failure, causing a complete collapse of army morale and discipline and sending hundreds of thousands of deserting troops streaming home. ( ii) The government had to share power with the Petrograd soviet, an elected committee of workers and soldiers representatives which tried to govern the city. Other soviets appeared in Moscow and all the provincial cities and when the Petrograd soviet ordered all soldiers to obey only the soviet, it meant that in the last resort the provisional government could not rely on the support of an army. (iii) Kerensky delayed the meeting of a Constituent Assembly (parliament) which he had promised and did nothing about land reform. This lost him support on all sides. (iv) Meanwhile, thanks to the new political amnesty. Lenin was able to return from exile in Switzerland (April). The Germans allowed him to travel through to Petrograd in a special 'sealed' train, in the hope that he would cause further chaos in Russia. After a rapturous welcome he urged that the soviets should cease to support the provisional government. (v) In the midst of general chaos, Lenin and the Bolsheviks put forward a realistic and attractive policy. He demanded all power to the soviets, and promised in return an end to the war, all land to he given to the peasants, and more food. By October the Bolsheviks were in control of both the Petrograd and Moscow soviets, though they were still in a minority over the country as a whole. (vi) On 20 October, urged on by Lenin, the Petrograd soviet took the crucial decision to attempt to seize power. Leon Trotsky, chairman of the soviet, made most of the plans, which went off without a hitch. During the night of 6-7 November, Bolshevik Red Guards occupied all key points and later arrested the provisional government ministers except Kerensky who managed to escape. It was almost a bloodless coup, enabling Lenin to set up a new soviet government with himself in charge. The coup had been successful because Lenin had judged to perfection the moment of maximum hostility towards the Kerensky government, and the Bolsheviks, who knew exactly what they wanted, were well disciplined and organised, whereas all other political groups were in disarray.

|

|

|

3.3 LENIN AND THE BOLSHEVIKS TAKE POWER 1917 The Bolsheviks were in control in Petrograd as a result of their coup, but elsewhere the takeover was not so smooth. Fighting lasted a week in Moscow before the soviet won control and it was the end of November before other cities were brought to heel. Country areas were much more difficult to deal with, and at first the peasants were lukewarm towards the new government, which very few people expected to last long because of the complexity or the problems facing it. As soon as the other political groups recovered their composure, there was bound to be determined opposition to the Bolsheviks, who had somehow to extricate Russia from the war and then set about repairing the shattered economy while at the same time keeping their promises about land and food for the peasants and workers.

|

|

|

3.4 HOW SUCCESSFUL WERE LENIN AND THE BOLSHEVIKS IN DEALING WITH THESE PROBLEMS (1917-24)?

(a) The Bolsheviks had nothing like majority support in the country as a whole; the problem was how to keep themselves in power once the public realised what a Bolshevik government involved. One of Lenin's first decrees therefore nationalised all land so that it could be redistributed among the peasants; this increased support for the Bolsheviks and was a great help in their fight with the Constituent Assembly. Lenin knew that he would have to allow elections, having criticised Kerensky so bitterly for postponing them, but he realised that a Bolshevik majority in the Assembly was highly unlikely. Elections were held (the only completely free and democratic elections ever to take place in Russia), but the Bolsheviks won only 168 seats out of about 700 while the right Social Revolutionaries had 380, a clear anti-Bolshevik majority. This would not do for Lenin who was aiming for a 'dictatorship of the proletariat', by which he meant that he and the Bolshevik party working through the soviets would run the country on behalf of the workers and peasants. There was no room in the scheme for any other party. Accordingly, after some anti-Bolshevik speeches at its first meeting (January 1918), the Assembly was dispersed by Bolshevik Red Guards and never met again. Armed force had triumphed for the time being, but opposition was to lead to civil war later in the year.

(b) The next pressing problem was how to withdraw from the war; an armistice between Russia and the Central Powers had been agreed in December 1917, but long negotiations followed, during which Trotsky tried without success to persuade the Germans to moderate their demands. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (March 1918) was cruel, Russia losing Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, the Ukraine, Georgia and Finland; this included a third of Russia's farming land, a third of her population, two-thirds of her coalmines and half her heavy industry. A terrible price indeed, but Lenin insisted that it was worth it, pointing out that Russia needed to sacrifice space in order to gain time to recover. He probably expected to get the land back anyway when, as he hoped. the revolution spread to Germany.

|

|

|

(c) By April 1918 armed opposition to the Bolsheviks was breaking out in many areas leading to civil war. The Whites were a mixed bag, including Social Revolutionaries, Mensheviks, ex-tsarist officers and any other groups which did not like what they had seen of the Bolsheviks; they were not aiming to restore the tsar, but simply to set up a parliamentary government on western lines. In Siberia Admiral Kolchak, former Black Sea Fleet commander, set up a White government; General Denikin was in the Caucasus with a large White army; most bizarre of all the Czechoslovak Legion of about 40,000 men had seized long stretches of the Trans-Siberian Railway in the region of Omsk. These troops were originally prisoners taken by the Russians from the Austro-Hungarian army, who had later fought against the Germans under the Kerensky government. After Brest-Litovsk the Bolsheviks gave them permission to leave Russia via the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostock, but then decided to disarm them in case they co-operated with the Allies, who were already showing interest in the destruction of the new Bolshevik government. The Czechs resisted with great spirit and their control of the railway was a serious embarrassment to the government. The situation was complicated by foreign intervention to help the Whites with the excuse that they wanted a government which would continue the war against Germany. When intervention continued even after the defeat of Germany. it became clear that the aim was to destroy the Bolshevik government which was now advocating world revolution. The USA, Japan, France and Britain sent troops, with landings at Archangel. Murmansk and Vladivostock. The situation seemed grim for the Bolsheviks when early in 1919 Kolchak (whom the Allies intended to head the next government) advanced with three armies towards Moscow, the new capital. However Trotsky, now Commissar for War, had done a magnificent job creating the well-disciplined Red Army, based on conscription and including thousands of experienced officers from the old tsarist armies. Kolchak was forced back, and later captured and executed by the Reds; the Czech legion was defeated and Denikin, advancing from the south to within 250 miles of Moscow, was forced to retreat; he later escaped with British help. By the end of 1919 it was clear that the Bolsheviks (now calling themselves communists) would survive, though 1920 saw an invasion of the Ukraine by Polish and French troops which forced the Russians to hand over part of the Ukraine and White Russia (Treaty of Riga 1921). From the communist point of view, however, the important thing was that they had won the civil war. The communist victory was achieved because: (i) The Whites were not centrally organised; Kolchak and Denikin failed to link up, and the nearer they drew to Moscow the more they strained their lines of communication. They lost the support of many peasants by their brutal behaviour and because peasants feared a White victory would mean the loss of their newly acquired land. (ii) The Red Armies had more troops plus the inspired leadership of Trotsky. (iii) Lenin took decisive measures, known as war communism, to control the economic resources of the state: all factories of any size were nationalised, all private trade banned, and food and grain seized from peasants to feed town workers and troops. This was successful at first in that it enabled the government to survive the civil war, but it had disastrous results later. (iv) Lenin was able to present the Bolsheviks as a nationalist government fighting against foreigners; and even though war communism was unpopular with peasants, the Whites became even more unpopular because of their foreign connections.

|

|

|

(d) From early 1921 Lenin had the formidable task of rebuilding an economy shattered by the First World War and then by civil war. War communism had been unpopular with the peasants who, seeing no point in working hard to produce food which was taken away from them without compensation, simply produced enough for their own needs. This caused severe food shortages aggravated by droughts in 1920-1. In addition industry was almost at a standstill. In March 1921 a serious naval mutiny occurred at Kronstadt, suppressed only through prompt action by Trotsky, who sent troops across the ice on the Gulf of Finland. This mutiny seems to have convinced Lenin that a new approach was needed to win back the faltering support of the peasants; he put into operation what became known as the New Economic Policy (NEP). Peasants were not allowed to keep surplus produce after payment of a tax representing a certain proportion of the surplus. This, plus the reintroduction of private trade, revived incentive and food production in-creased. On the other hand heavy industry was left under state control, though some smaller factories were handed back to private ownership; Lenin also found that often the old managers had to be brought back, as well as such capitalist incentives as bonuses and piece-rates. Lenin saw NEP as a temporary compromise - a return to a certain amount of private enterprise until recovery was assured; his long-term aim remained full state control of industry, and of agriculture (through collective farms). Gradually the economy began to recover, though there were recurrent food shortages for many years.

(e) Political problems were solved with typical efficiency. Russia was now the world's first communist state, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) with power held by the communist party (no other parties were allowed). In March 1921 Lenin banned groups who criticised his policies within the party, and during the rest of that year about one-third of the party members were 'purged' or expelled with the help of the ruthless secret police (OGPU). Control by Lenin and the party was complete. (For his successes in foreign affairs see Section 13.3(a) and (b).) In May 1922 Lenin had his first stroke; after this he gradually grew weaker, suffering two more strokes until he died in January 1924 at the early age of 53. A. J. P. Taylor sums up his career well: 'Lenin did more than any other political leader to change the face of the twentieth-century world. The creation of Soviet Russia and its survival were due to him. He was a very great man and even, despite his faults. a very good man.'

|

|

Chapter 9. STALIN AND THE USSR, 1924-39Summary of Events Russia during this period was dominated by one man - Joseph Stalin - who, as dictator until his death in 1953 at the age of 73, wielded as much power as ever the tsars had done before him. When Lenin died in January 1924 it was widely expected that Trotsky would take over as leader. but a complex power struggle developed from which Stalin had emerged triumphant by the end of 1929. Immense problems faced communist Russia. still only a few years old: industry and agriculture were backward and inefficient, there were constant food shortages, pressing political and social problems - and, many Russians thought, the danger of another attempt by foreign capitalist powers to destroy the new communist state. Stalin made determined efforts to overcome all these problems: there were the Five Year Plans to revolutionise industry, the collectivisation of agriculture and the introduction of a totalitarian regime which was, if anything. more ruthlessly efficient than Hitler's system in Germany. Yet, brutal though Stalin's methods were. they seem to have been successful, at least to the extent that when the dreaded attack from the west eventually came in the form of a massive German invasion in June 1941, the Russians were able to hold out and eventually end up on the winning side, though admittedly at a terrible cost.

|

|

|

9.1 HOW DID STALIN MANAGE TO GET TO SUPREME POWER? Joseph Djugashvili (he took the name 'Stalin' - man of steel - some time after joining the Bolsheviks in 1904) was born in 1879 in the small town of Gori in the province of Georgia; his parents were poor peasants; in fact his father, a shoemaker, had been born a serf. Joseph's mother wanted him to become a priest and he was educated for four years at Tiflis Theological Seminary, but he hated its repressive atmosphere and was expelled in 1899 for expounding socialist principles. He became a Bolshevik about 1904 and after 1917, thanks to his brilliance as an administrator, he was quietly able to build up his own position under Lenin. When Lenin died in 1924 Stalin was Secretary-General of the communist party and a member of the seven-man Politburo, the commit-tee which decided government policy. At first it seemed unlikely that Stalin would become the dominant figure; Trotsky called him 'the party's most eminent mediocrity', and Lenin thought him stubborn and rude, and suggested in his will that Stalin be removed from his post. The most obvious successor to Lenin was Trotsky, an inspired orator, an intellectual, and the organiser of the Red Armies. However, circumstances arose which Stalin was able to use to eliminate his rivals:

(a) Trotsky's brilliance worked against him by arousing envy and resentment among the other Politburo members who combined to prevent his becoming leader: collective action was better than a one-man show.

(b) The Politburo members underestimated Stalin, seeing him as nothing more than a competent administrator; they ignored Lenin's advice.

(c) As Secretary-General of the party, Stalin had full powers of appointment and promotion, which he used to place his own supporters in key positions while at the same time removing the supporters of odic is to distant parts of the country.

(d) Stalin used the disagreements in the Politburo over policy to his own advantage. These arose partly because Marx had never described in detail exactly how the new communist society should be organised and even Lenin was vague about it, except that 'the dictatorship of the proletariat' would be established - that is, workers would run the state and the economy in their own interests. When all opposition had been crushed, the ultimate goal of a classless society would be achieved in which, according to Marx, the ruling principle would be: 'from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs'. With NEP (the New Economic Policy: see Section 3.3(d)) Lenin had departed from socialist principles, though this would only be a temporary measure until the crisis passed. Now the right, led by Bukharin, and the left, whose views were most strongly put by Trotsky, fell out about what to do next: (i) Bukharin wanted to continue NEP, even though it was causing an increase in numbers of kulaks. His opponents wanted to abandon NEP and concentrate on rapid industrialisation at the expense of the peasants. (ii) Bukharin thought it important to consolidate soviet power in Russia, based on a prosperous peasantry and with a very gradual industrialisation - 'socialism in one country', as it became known. Trotsky believed that they must work for revolution outside Russia - `permanent revolution'; when this was achieved the industrialised states of western Europe would help Russia with her industrialisation. Stalin, quietly ambitious, apparently had no strong views either way at first, but he supported the right simply to isolate Trotsky. Later, when a split occurred between Bukharin and two other Politburo members, Zinoviev and Kamenev, who were feeling unhappy about NEP, Stalin supported Bukharin, and one by one Trotsky, Zinoviev and Kamenev were voted off the Politburo by Stalin's yes-men and expelled from the party (1927). The following year Stalin decided that NEP must go - the kulaks were holding up agricultural progress; when Bukharin protested, he too was expelled (1929) and Stalin was left supreme. Having reached the pinnacle, Stalin attacked the many problems facing Russia, which fell into three categories: economic, political and social. and foreign (see Section 13.3).

|

|

|

9.2 WHAT WERE THE ECONOMIC PROBLEMS, AND HOW SUCCESSFUL WAS STALIN IN SOLVING THEM? (a) The problems (i) Although Russian industry was recovering from the effects of the war, production from heavy industry was still surprisingly low; in 1929 for example, France, not a major industrial power, produced more coal and steel than Russia, while Germany, Britain and especially the USA were streets ahead. Stalin believed that a rapid expansion of heavy industry was essential so that Russia would be able to survive the attack which he was convinced would come sooner or later from the Western capitalist powers who hated communism. Industrialisation would have the added advantage of increasing support for the government, because it was the industrial workers who were the communists' greatest allies: the more industrial workers, the more secure the communist state would be. One serious obstacle to overcome, though, was lack of capital to finance expansion, since foreigners were unwilling to invest in a communist state. (ii) More food would have to be produced, both to feed the growing industrial population and to provide a surplus for export which would bring in foreign capital and profits for investment in industry. Yet the primitive agricultural system was incapable of providing such increases.

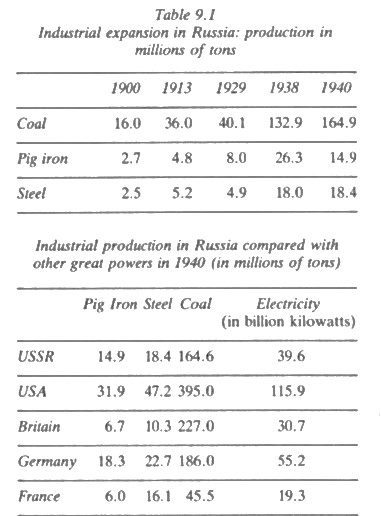

(b) The approach Although he had no economic experience whatsoever, Stalin seems to have had no hesitation in plunging the country into a series of dramatic changes designed to overcome the problems in the shortest possible time. In a speech in February 1931 he explained why: 'We are 50 or 100 years behind the advanced countries. We must make good this distance in 10 years. Either we do it, or we shall be crushed.' NEP had been permissible as a temporary measure, but must now be abandoned: both industry and agriculture must be taken under government control. (i) Industrial expansion was tackled by a series of Five Year Plans, the first two of which (1928-32 and 1933-7) were said to have been completed a year ahead of schedule. though in fact neither of them reached the full target. The first plan concentrated on heavy industry - coal, iron, steel, oil and machinery (including tractors), which were scheduled to triple output; the two later plans provided for some increases in consumer goods as well as in heavy industry. It has to be said that in spite of all sorts of mistakes the plans were a remarkable success: by 1940 the USSR had overtaken Britain in iron and steel production, though not yet in coal, and she was within reach of Germany:

Hundreds of factories were built, many of them in new towns east of the Ural Mountains where they would be safer from invasion. Well-known examples are the iron and steel works at Magnitogorsk, tractor works at Kharkov and Gorki, a hydro-electric dam at Dnepropetrovsk and the oil refineries in the Caucasus. How was it achieved? The cash was provided almost entirely by the Russians themselves, with no foreign investment; some came from grain exports, some from charging peasants heavily for use of government equipment and the ruthless ploughing back of all profits and surplus. Hundreds of foreign technicians were brought in and great emphasis placed on expanding education in technical colleges and universities and even in factory schools, to provide a whole new generation of skilled workers. In the factories the old capitalist methods of piecework and pay differentials between skilled and unskilled workers were used to encourage production; medals were given to workers who achieved record output; these were known as Stakhanovites after Alexei Stakhanov, a champion miner who in August 1935, supported by a well-organised team, managed to cut 102 tons of coal in a single shift (by ordinary methods even the highly efficient miners of the Ruhr in Germany were managing only 10 tons per shift). Ordinary workers were ruthlessly disciplined: there were severe punishments for had workmanship, accusations of being a 'saboteur' when targets were not met and often a spell in a forced labour camp. Primitive housing conditions and a severe shortage of consumer goods (because of the concentration on heavy industry) on top of all the regimentation must have made life grim for most workers. As Richard Freeborn points out: 'It is probably no exaggeration to claim that the First Five Year Plan represented a declaration of war by the state machine against the workers and peasants of the USSR who were subjected to a greater exploitation than any they had known under capitalism.' However, by the mid- 1930s things were improving as benefits such as education, medical care and holidays with pay became available.

|

|

|

(ii) The problems of agriculture were dealt with by the process known as collectivisation. The idea was that the small farms and holdings belonging to the peasants should be merged to form large collective farms jointly owned by the peasants. There were two main reasons for Stalin's decision to collectivise: - The existing system of small farms was inefficient, whereas large farms, under state direction and using tractors and combine harvesters, would vastly increase grain production. - He wanted to eliminate the class of prosperous peasants (kulaks or nepmen) which NEP had encouraged because, he claimed, they were standing in the way of progress. But the real reason was probably political: Stalin saw the kulak as the enemy of communism. 'We must smash the kulaks so hard that they will never rise to their feet again.' The policy was launched in earnest in 1929, and had to be carried through by sheer brute force, so determined was the resistance in the countryside. It was a complete disaster from which. it is probably no exaggeration to claim. Russia has not fully recovered even today. There was no problem in collectivising landless labourers, but all peasants who owned any property at all, whether they were kulaks or not, were hostile and had to be forced to join by armies of party members who urged poorer peasants to seize cattle and machinery from the kulaks to be handed over to the collectives. Kulaks often reacted by slaughtering cattle and burning crops rather than allow the state to take them. Peasants who refused to join collective farms were arrested and deported to labour camps or shot; when newly collectivised peasants tried to sabotage the system by producing only enough for their own needs, local officials insisted on seizing the required quotas, resulting in large-scale famine during 1932-3, especially in the Ukraine. Yet one and three-quarter million tons of grain were exported during that period while over five million peasants died of starvation. Some historians have even claimed that Stalin welcomed the famine, since, along with the 10 million kulaks who were removed or executed, it helped to break peasant resistance. In this way, well over 90 per cent of all farmland had been collectivised by 1937. In one sense, Stalin could claim that collectivisation was a success; it allowed greater mechanisation, which gradually increased grain output until by 1940 it was over 80 per cent higher than in 1913. On the other hand, so many animals had been slaughtered that it was 1953 before livestock production recovered to the 1928 figure and the cost in human life and suffering was enormous.

|

|

|

9.3 POLITICAL AND SOCIAL PROBLEMS, AND STALIN'S SOLUTIONS (a) The problems were to some extent of Stalin's own making; he obviously felt that under his totalitarian regime, political and social activities must be controlled just as much as economic life: he aimed at complete and unchallenged power for himself and became increasingly suspicious and intolerant of criticism. (i) Starting in 1930, there was growing opposition within the party which aimed to slow down industrialisation. allow peasants to leave collective farms, and remove Stalin from the leadership if necessary. However. Stalin was equally determined that political opponents and critics must be eliminated once and for all. (ii) A new constitution was needed to consolidate the hold of Stalin and the communist party over the whole country. (iii) Social and cultural aspects of life needed to he brought into line and harnessed to the service of the state.

(b) Stalin's methods were typically dramatic. (i) Using the murder of Sergei Kirov, one of his supporters on the Politburo (December 1934), as an excuse, Stalin launched what became known as the purges. It seems fairly certain that Stalin himself organised Kirov's murder, 'the crime of the century', as Robert Conquest calls it, 'the keystone of the entire edifice of terror and suffering by which Stalin secured his grip on the Soviet peoples'. but it was blamed on Stalin's critics. Over the next four years hundreds of important officials were arrested, tortured, made to confess to all sorts of crimes of which they were largely innocent (such as plotting with the exiled Trotsky or with capital-ist governments to overthrow the soviet state) and forced to appear in a series of 'show trials' at which they were invariably found guilty and sentenced to death or labour camp. Those executed included all the 'Old Bolsheviks' - Zinoviev, Kamcnev, Bukharin and Radek - who had helped to make the 1917 revolution, the Commander-in-Chief of the Red Army, Tukhachevsky, thirteen other generals and about two-thirds of the top officers; millions of innocent people ended up in labour camps (Conquest puts the figure at about eight million by 1938). Even Trotsky was sought out and murdered in exile in Mexico City, though he managed to survive until 1940. The purges were successful in eliminating possible alternative leaders and in terrorising the masses into obedience, but the consequences were serious: many of the best brains in the government, the army and in industry had disappeared, and in a country where the highly educated class was still small, this was bound to hinder progress. (ii) In 1936, after much discussion, a new and apparently more democratic constitution was introduced in which everyone was allowed to vote by secret ballot for members of a national assembly known as the Supreme Soviet. However, this met for only about two weeks in the year, when it elected a smaller body, the Praesidium, to act on its behalf, and when it also chose the Union Soviet of Commissars. a small group of ministers of which Stalin was the Secretary, and which wielded the real power. In fact the democracy was an illusion: the constitution merely underlined the fact that Stalin and the party ran things. and though there was mention of freedom of speech, anybody who ventured to criticise Stalin was quickly 'purged'. (iii) Writers, artists and musicians were expected to produce works of realism glorifying soviet achievements; anybody who did not conform was persecuted, and even those who tried often still fell foul of Stalin. The young composer Shostakovich was condemned when his new opera, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, failed to please Stalin, even though the music critics had at first praised it. Further performances were banned with the result, according to the American ambassador, that 'half the artists and musicians in Moscow are having nervous prostration and the others are trying to imagine how to write and compose in a manner to please Stalin'. Education like everything else was closely watched by the secret police, and although it was compulsory and free it tended to deteriorate into indoctrination; but at least literacy was increased, which along with the improvement in social services, was an unprecedented achievement. Finally an attempt was made to clamp down on the Orthodox Church: churches were closed and clergy persecuted; but this was one of Stalin's failures: in 1940 probably half the population were still convinced believers, and during the war the persecution was relaxed to help maintain morale.

|

|

|

9.4 WAS THE STALIN APPROACH NECESSARY? Historians have failed to agree about the extent of Stalin's achievement, or indeed whether he achieved any more with his brutality than could have been managed by less drastic methods. Stalin's defenders, who include many soviet historians, argue that the situation was so desperate that only the pressures of brute force could have produced such a rapid industrialisation together with the necessary food; for them, the supreme justification is that thanks to Stalin Russia was strong enough to defeat the Germans. The opposing view is that Stalin's policies, though superficially successful, actually weakened Russia: ridiculously high targets for industrial production placed unnecessary pressure on the workers and caused slipshod work and poor quality products; the brutal enforcement of collectivisation vastly reduced the amount of meat available and made peasants so bitter that in the Ukraine the German invaders were welcomed; the purges slowed economic progress by removing many of the most experienced men, and almost caused military defeat during the first months of the war by depriving the army of all its experienced generals; in fact Russia won the war in spite of Stalin, not because of him. Whichever view one accepts, a final point to bear in mind is that many Marxists outside Russia feel that Stalin betrayed the idealism of Marx and Lenin: instead of a new classless society in which everybody was free and equal, ordinary workers and peasants were just as exploited as under the tsars, whereas skilled workers were an Elite; the party had taken the place of the capitalists, and enjoyed all the privileges - the best houses, country retreats and cars. Instead of Marx's 'dictatorship of the proletariat' there was merely the dictatorship of Stalin.

|

|

|

| |