17.2 WAR IN KOREA, 1950-53

Soon after the communist victory in China civil war broke out in Korea.

Its origins lay in the fact that the Country had been divided into two zones in

1945 at the end of the Second World War.

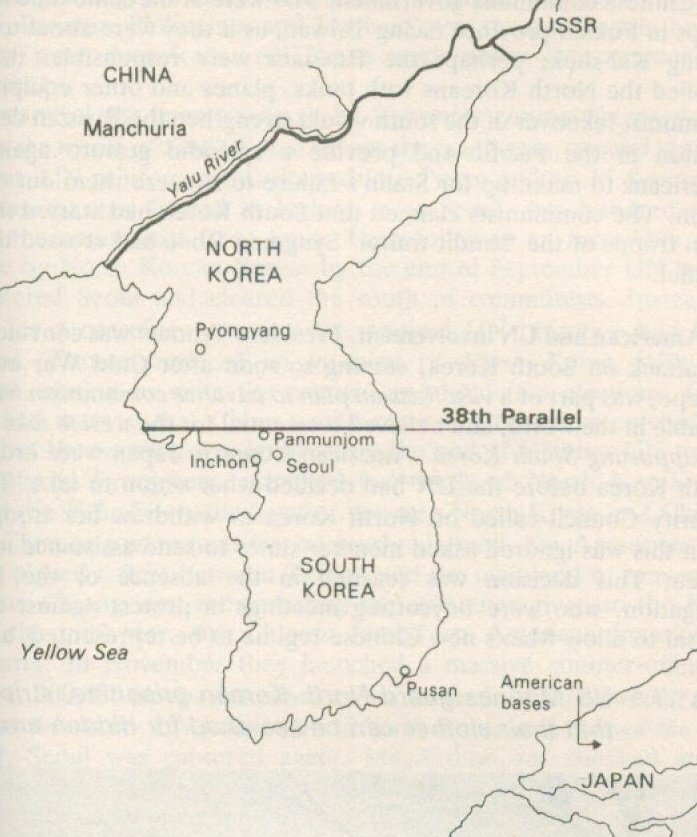

(a) Korea was divided into two at the 38th parallel by agreement between the USA and the USSR for purely military reasons – so that they could organise the surrender of the occupying Japanese forces; it was not intended to be permanent political division. The United Nations wanted free elections for the whole country and the Americans agreed, believing that since their zone, the South, contained two-thirds of the population, the communist N would be outvoted. However the unification of Korea, like that that of Germany, soon became part of the Cold War rivalry and no agreement could be reached. Elections were held in the South, supervised by the UN, and the independent Republic of Korea (ROK) or South Korea or set up with Syngman Rhee as president and its capital at Seoul (August 1948). The following month the Russians created the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea or North Korea under the communist government of Kim Il Sung, with its capital at Pyongyang. In 1949 Russian and American troops were withdrawn, leaving a potentially dangerous situation: most Koreans bitterly resented the artificial division forced on their country by outsiders, but both leaders claimed the right to rule the whole country.

Without warning, North Korean troops invaded South Korea in June 1950.

(b) There is some controversy about the origins of the attack. It is still not clear whether it was Kim Il Sung’s idea, perhaps encouraged by General MacArthur’s statement in 1949 that Korea was no longer part of the US defence perimeter in the Pacific; or he may have been egged on by the new Chinese communist government who were at the same time massing troops in Fukien province facing Taiwan, as if they were about to attack Chiang Kai-shek; perhaps the Russians were responsible: they had supplied the North Koreans with tanks, planes and other equipment; a communist takeover of the south would strengthen the Russian defensive position in the Pacific and provide a splendid gesture against the Americans to make up for Stalin’s failure to squeeze them out of West Berlin.

The communists claimed that South Korea had started the war, when troops of the

‘bandit traitor’ Syngman Rhee had crossed the 38th parallel.

(c) American and UN involvement. President Truman was convinced that the attack on South Korea, coming so soon after Cold War events in Europe, was part of a vast Russian plan to advanced communism wherever possible in the world, and believed it is central for the West to take a stand by supporting South Korea. American troops in Japan were ordered to South Korea before the UN had decided what action to take. The UN Security Council called on North Korea to withdraw her troops, and when this was ignored asked member states to send assistance to South Korea. This decision was reached in the absence of the Russian delegation, who were boycotting meetings in protest against the UN refusal to allow Mao’s new Chinese regime to be represented and who would certainly have vetoed such a decision.

In the event, the USA and fourteen other countries (Australia, Britain, Canada,

New Zealand, nationalist China, France, Netherlands, Belgium, Columbia, Greece,

Turkey, Panama, Philippines and Thailand) send troops, though the vast majority

were Americans feel stuck all forces were under the command of MacArthur.

Their arrival was just in time to prevent the whole of South Korea from being overrun by the communists. By September, communist forces had captured the whole country except the south-east, around the port of Pusan. UN reinforcements poured into Pusan and on 15 September, American marines landed at Inchon, near Seoul, 200 miles behind the communist front lines. Then followed an incredibly swift collapse of the North Korean forces: by the end of September UN troops had entered Seoul and cleared the south of communists. Instead of calling for a ceasefire, now that the original UN objective had been achieved, Truman ordered an invasion of North Korea, with UN approval, aiming to unite the country and hold free elections. The Chinese Foreign Minister Zhou Enlai (Chou En-lai) warned that China would resist if UN troops entered North Korea, but the warning was ignored.

By the end of October, UN troops had captured Pyongyang, occupied two-thirds of

North Korea and reached the River Yalu, the frontier between North Korea and

China.

The Chinese government was seriously alarmed, the Americans had already placed a fleet between Taiwan and the mainland to prevent an attack on Chiang, and there seemed every chance that they would now invade Manchuria (the part of China bordering on North Korea). In November therefore, the Chinese launched a massive counter-offensive with over 300 000 troops, described as ‘volunteers’; by mid-January 1951 they had driven the UN troops out of North Korea, crossed the 38th parallel and captured Seoul again. MacArthur was shocked at the strength of the Chinese forces and argued that the best way to defeat communism was to attack Manchuria, with atomic bombs if necessary. However, Truman thought this would provoke a large-scale war, which the USA did not want, so he decided to settle for merely containing communism ; MacArthur was removed from his command. In June UN troops cleared the communists out of South Korea again and fortified the frontier.

Peace talks opened in Panmunjom and lasted for two years, ending in July 1953

with an agreement that the frontier should be roughly along the 38th parallel,

where it had been before the war began.

(d) The results of the war were wide-ranging. For Korea itself it was a disaster: the country was devastated, about four million Korean soldiers and civilians had been killed and five million people were homeless. The division seemed permanent; both states remained intensely suspicious of each other and heavily armed, and there were constant ceasefire violations. The USA could take some satisfaction from having contained communism and could claim that this success, plus American rearmament, dissuaded world communism from further aggression. The UN had exerted its authority and reversed an act of aggression, but the communist world denounced it as a tool of the capitalists. The military performance of communist China was impressive; she had prevented the unification of Korea under American influence and was now clearly a world power. The fact that she was still not allowed a seat in the UN seemed even more unreasonable. The conflict brought a new dimension to the Cold War. American relations were now permanently strained with China as well as with Russia; the familiar pattern of both sides trying to build up alliances appeared in Asia as well as Europe. China supported the Indo-Chinese communists in their struggle for independence from France, and at the same time offered friendship and aid to under-developed ‘Third World’ countries in Asia, Africa and Latin America; ‘peaceful coexistence’ agreements were signed with India and Burma (1954). Meanwhile the Americans tried to encircle China with bases: in 1951 defensive agreements were signed with Australia and New Zealand, and in 1954 these three states, together with Britain and France, set up the South East Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). However, the USA was disappointed when only three Asian states - Pakistan, Thailand and the Philippines - joined SEATO.

It was obvious that many states wanted to keep clear of the Cold War and remain

uncommitted.

Relations between the USA and China were also poor because of the Taiwan situation.

The communists still hoped to capture the island and destroy Chiang Kai-shek and

his Nationalist Party for good; but the Americans were committed to defending

Chiang and wanted to keep Taiwan as a military base.

|

|