|

|

|

|

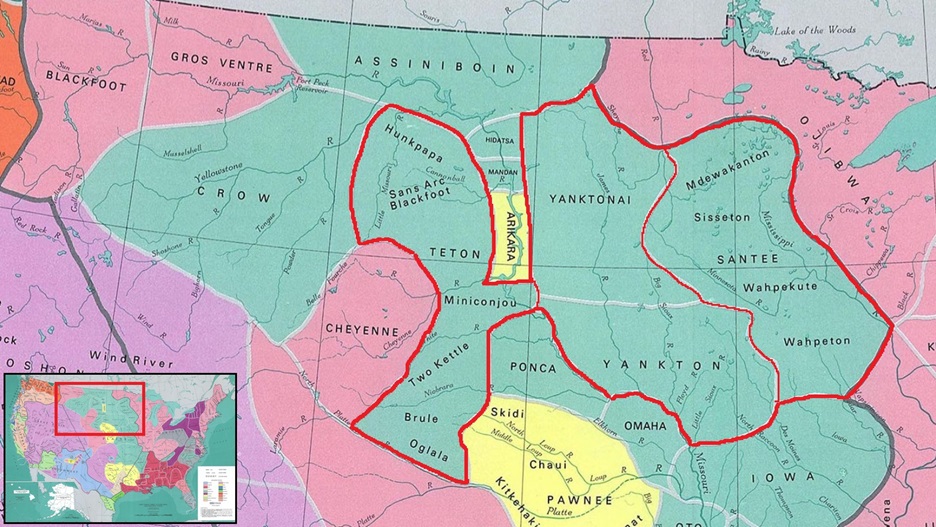

This map of the Oceti Sakowin Nation is taken from this much larger modern map of the Indigenous Nations and their languages.

|

Going DeeperThe following links will help you widen your knowledge: YouTube |

GovernmentThe Indigenous Nations’ way of ‘government’ led some early settlers to think that they had no government at all. The basis of Sioux government was the thiyospaye (‘camp circle’). The people of the Great Sioux Nation refer to themselves as the Oceti Sakowin (‘Seven Council Fires’) – a reference to the seven tribes whose leaders gathered at the annual summer thiyospaye. The seven tribes divided roughly into three groups – called in English the Lakota (or Teton), the West Dakota (or Yankton/Yanktonai) and the East Dakota (or Santee). Each of the seven tribes had their own thiyospaye:

Since the harsh environment forced them to work together, there were no written laws or prisons; a Sioux’s only duty was to pray. Breaches of the social code were punished by shaming, and the worst punishment was banishment.

Source AOur fathers gave us many laws, which they had learned from their fathers. These laws were good. They told us to treat all men as they treated us; that we should never be the first to break a bargain; that it was a disgrace to tell a lie; that we should speak only the truth; that it was a shame for one man to take from another his wife, or his property without paying for it. We were taught to believe that the Great Spirit sees and hears everything, and that he never forgets; that hereafter he will give every man a spirit-home according to his deserts: if he has been a bad man, he will have a bad home. This I believe, and all my people believe the same.... In-mut-too-yah-lat-lat (Thunder traveling over the Mountains), quoted in the North American review (1879). In-mut-too-yah-lat-lat – known to white Americans as Chief Young Joseph – was Chief of the Nez Percé tribe in Oregon. This was the second paragraph of a 17-page speech in which he outlined all the times the white-faced men and lied to and cheated his people.

Source BNothing is more difficult to understand than the government of an Indian tribe… I cannot say exactly how the powers and duties of the three governmental forms [Chief, Council and Warrior societies] blend and concur … and I have never met an Indian or white man who could satisfactorily explain them. The result, however, is fairly good, and seems well suited to the character, necessities, and peculiarities of the life of the plains Indian. Colonel Richard Dodge, Hunting Grounds of the Great West (1877). Dodge was a cavalry colonel who – accompanied by George Catlin – led an expedition in 1834 to establish friendly contact with the Comanche Nation. Although not hostile towards the Indigenous Peoples, he saw them through his eyes as an army officer and, suggested Martin & Shephard (1998), "did not wholly understand them".

|

Did You KnowThe word ‘Sioux’ means ‘snake’. When the French asked the Ojibwa, with whom the Sioux were at war, what they were called, they were told 'little snakes', meaning 'enemy'. The French, hearing 'Nadouessioux', shortened it to 'Sioux'. The Sioux people refer to their Nation as Oceti Sakowin, meaning 'Seven Council Fires' – a refernce to the seven tribes which make up the Great Sioux Nation.

|

WarfareThe most common reason for war between tribes and nations was to get horses: a warrior was judged by the number of horses that he owned, and horses were an accepted currency, so many tribes raided each other and were raided back in revenge, the aim being to capture horses and to show bravery. Although the Indigenous Nations fought wars which included massacres and many deaths, the general opinion was that fighting to the death was stupid because men were so valuable in the buffalo hunt; a warrior needed to stay alive to care for their family and community. No one was FORCED to go to war – individual warriors chose to follow the Chief to war or not as they felt best – and most battles were short, often involving ambushes and quick raids, and a brave warrior lived to fight another day. ‘Counting coup’ was considered the bravest act of war. This involved the warrior touching his enemy with a coup stick. This meant that he was skilful enough to get close to his enemy but did not value him enough to kill him. A warrior’s battle dress often showed how many times he had counted coup. Indians used tomahawks and bows and arrows in their hunting and warfare. When they died, the Sioux believed that they would go to the Happy Hunting Ground; there was no Heaven or Hell but they would meet everyone they had met in life in the Happy Hunting Ground. They would therefore try to prevent their enemies from being whole in the Happy Hunting Ground; if they did kill anyone they would scalp them or cut their ankle or wrist tendons so that they could not run or fire arrows in the Happy Hunting Ground.

|

Did You KnowWhile Native Americans might try to steal the horses

under cover of night, they rarely attacked a wagon train, though smaller,

badly-organised groups were in more danger. Wagon trains which were

just passing though were usually tolerated, and indeed depended for their

survival on trade with the local tribes.

|

Source CIn fighting with white men, a surprise is always made when possible ... the Indians can always avoid a battle, and would never be brought to accept it unless they outnumbered the soldiers at least five to one... There is one well-authentcated instance of a fair stand-up fight between nearly equal numbers of troops and Indians. The Indian's great delight is the attack of a waggon train. There is comparatively little risk, and his reward in ponies and plunder most ample. For days he will watch the slow moving line, until he knows exactly the number and character of armed men that defend it... He lies in wait, and at the proper time rushes out with terrifying yells, frightening the teams, which run away, overturning waggons, and throwing everything into confusion. If a direct attack involves too much risk, the Indian's next concern is to get possession of the horses and mules... Colonel Richard Dodge, Hunting Grounds of the Great West (1877).

|

Consider:1. Suggest ways in which the Sioux government was "well suited to their character, necessities, and peculiarities of life"? 2. Would it be possible to say the same about their way of warfare?

|

|

|

|

|

Spotted an error on this page? Broken link? Anything missing? Let me know. |

|