Life in Tudor Towns

Introduction

This true story is taken from the 1972 book, Policy and Police, by the renowned historian G.R.Elton:

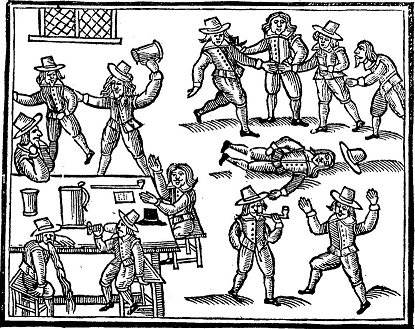

A man called John Smith and two women went into a tavern (a pub) near St Bride's Church in London. They were waiting to be served when a crowd of people came in, led by William Kyng, an apprentice. Kyng called for some wine, and he and his friends were served.

A man called John Smith and two women went into a tavern (a pub) near St Bride's Church in London. They were waiting to be served when a crowd of people came in, led by William Kyng, an apprentice. Kyng called for some wine, and he and his friends were served.

At this, Smith rose out of his seat, and went over to William Kyng, saying, 'Thou whoreson, why takest thou my wine?' When Kyng protested that it was his own wine, Smith 'out of cruel evil took the said pot of wine and hit the aforesaid William on the head'. He also took his dagger out. The other customers stopped the fight, and sent Kyng and his friends away.

Kyng went to another tavern, called The Standard, with two friends. One of them saw a man and shouted, 'Yonder goes he that hit thee in the tavern.' In fact, he had made a mistake. It was not John Smith. It was a law student called Oystreche, from Clifford's Inn (one of the law schools near London).

Kyng and his friends stopped Oystreche, who seemed confused. 'I know thee not, nor yet did I hit thee,' he said. Kyng hit Oystreche, who ran to a nearby house. The people who lived there stopped the fight. Kyng realised he had attacked the wrong man. He said he was sorry.

Sorry, however, was not good enough for Oystreche. He went back to Clifford's Inn and collected a crowd of his friends. They went down into London to complain to Kyng's master. Kyng's master said he was sorry and that he would deal with the matter, and everyone went home.

Everyone, that is, except two young law students. They took some weapons and hid in 'an alley going down to the river by Fleet Bridge'. They planned to ambush William Kyng. Instead, in another case of mistaken identity, they attacked one John Penyngton – a bow-and-arrow maker – who was innocently making his way home. Penyngton screamed for help. The attackers were arrested and taken to the constable.

When the students at Clifford's Inn heard what had happened, they put on their 'armour with axes and long and short swords'. Then they swarmed back into London to rescue their friends. The men of St Bride's formed a gang and drove them back after a fierce battle.

The constable was too scared to arrest anyone, and the matter was forgotten.

After you have studied this webpage, answer the question sheet by clicking on the 'Time to Work' icon at the top of the page.

Links:

The following websites will help you research further:

Tudor Violence:

• Why were the Tudors so violent -

shocking video; disturbing scenes • The Daily Mail article on

binge drinking in Tudor times

1 The Armourer's House, by Rosemary Sutcliff

This passage is taken from The Armourer's House, by Rosemary Sutcliff – a children's book written in the 1950s about Tamsyn, a lttle girl living in Tudor London.

In those days cities were not at all like they are now. They were small and compact and cosy. The houses were cuddled close together inside their city walls, with the towers of their cathedrals standing over them to keep them safe

from harm. London was like that. As you came towards it, up the Strand from Westminster or over the meadows from Hampstead, you could see the towers and spires and steep roofs of the City rising above its protecting walls as gay as flowers in a flower-pot; and when you had passed through the gates (there were eight fine gates to London Town), the

streets were narrow and crooked and very dirty, but bright with swinging shop-signs and hurrying crowds. And the shops under the brilliant signs were as gay as fairground booths, with broidered gloves and silver hand-mirrors, jewels to hang in ladies' ears, baskets of plaited rushes, coifs of bone lace, wooden cradles hung with little golden bells for wealthy babies. Other shops sold the rare and lovely things from overseas that were still new to the English people – Venetian goblets as fine as soap bubbles, pale eastern silks, strange spices for rich men's tables, and musk in little flasks for people to make themselves smell nice. But if you wanted ordinary things, such as food or preserving pans, you went to Cheapside or some other market; and if you wanted herbs you went to the herb market, which was really one of the loveliest places in London, because most flowers and green things counted as herbs in those days.

In those days cities were not at all like they are now. They were small and compact and cosy. The houses were cuddled close together inside their city walls, with the towers of their cathedrals standing over them to keep them safe

from harm. London was like that. As you came towards it, up the Strand from Westminster or over the meadows from Hampstead, you could see the towers and spires and steep roofs of the City rising above its protecting walls as gay as flowers in a flower-pot; and when you had passed through the gates (there were eight fine gates to London Town), the

streets were narrow and crooked and very dirty, but bright with swinging shop-signs and hurrying crowds. And the shops under the brilliant signs were as gay as fairground booths, with broidered gloves and silver hand-mirrors, jewels to hang in ladies' ears, baskets of plaited rushes, coifs of bone lace, wooden cradles hung with little golden bells for wealthy babies. Other shops sold the rare and lovely things from overseas that were still new to the English people – Venetian goblets as fine as soap bubbles, pale eastern silks, strange spices for rich men's tables, and musk in little flasks for people to make themselves smell nice. But if you wanted ordinary things, such as food or preserving pans, you went to Cheapside or some other market; and if you wanted herbs you went to the herb market, which was really one of the loveliest places in London, because most flowers and green things counted as herbs in those days.

The street of the Dolphin House was one of the nicest streets in London. It was a very busy street, full of a great coming and going that went on all the daylight hours, so that there was always something to watch from the windows... Brown-clad monks, and church carvers and candle-makers, merchants and yet more merchants, and jewellers and silversmiths, and sailors everywhere – more sailors every day, it seemed to Tamsyn. All these came and went along the street, and sometimes a great lord would ride by on a tall horse, or a lady with winged sleeves of golden gauze and servants running ahead to clear the way lather.

Strolling players often passed that way, too, on their way from Ludgate to

the Fountain Tavern, where they acted their plays; and Morris Dancers, or a

performing bear led by a little boy, or a man with a cadge of hawks for

sale...

Oh, it was a very exciting street, and as the

weeks went by, Tamsyn began to like it very much indeed.